Even in the Era of AI, Plagiarism is Still Bad

-

Jonas Trinidad

- Blogs

-

October 30 , 2025

October 30 , 2025 -

10 min read

10 min read

Back in my childhood, my brother and I would create random content together for fun. One example I remember was making our own fictional list of Pokémon gym leaders, complete with towns and their Pokémon lineup. It was the franchise’s height at the time, so we were understandably stoked about making these fan-made works.

However, there were times when we had a falling out while making our lists. It was mostly my fault, as I was impressed by my brother’s lineup and couldn’t help but mimic his style. He’d grow livid, and my young, dumb self was none the wiser as to why.

Later in life, I understood the reason for his anger. No one appreciates a copycat, whether or not they intend to profit from it. Content creators, be it writers or filmmakers, should understand this more than anyone. I’ve outgrown Pokémon, but the lesson stuck with me.

Okay, plagiarism is bad. End of story, right?

A Tangled Mess Just Got Messier

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines plagiarism as:

“An act or instance of plagiarizing.”

Okay, moving on. The dictionary defines “plagiarize” as:

“To steal and pass off (the ideas or words of another) as one’s own, use (another’s production) without crediting the source.”

Defining plagiarism is as easy as opening a dictionary, physical or online. The problem lies with proving that a piece of content passes as one. In his autobiography, Mark Twain (real name Samuel L. Clemens) stated that there’s no such thing as a new idea. Instead, people take a couple of existing ideas to turn them into new combinations. (1)

Most people don’t see this as a problem as long as it results in a novel idea, though some go to litigation to insist otherwise. Not long ago, people entertained the thought of paying royalties every time they sang Happy Birthday.

Then AI came along and made plagiarism more complicated.

Generative AI’s capabilities in content creation are nothing to scoff at. Save for the minds behind the technology, who else would’ve thought that all it would take to create a write-up or work of art is a few prompts? On that note, who’s to say how generative AI will work 10 or 100 years from now?

But right now, technology raises as many questions as it provides answers. Suppose a person uses ChatGPT or Gemini to create an image. Who should be credited as the artist?

- The AI user: As the one who made the image (or a request), shouldn’t the user be credited? The problem with this thinking is that typing prompts onto a state-of-the-art machine isn’t exactly a skill in the same league as drawing and coloring.

- Other artists: Surely the credit should go to the artists whose works were used to train the AI model for the tool. However, that’s assuming you can sort out what art belongs to whom out of the countless works used as training data.

- The AI tool: Should the credit go to the tool? Or, to an extent, the tool’s developers? In some countries, a tool can’t be an author because their intellectual property laws prevent non-humans from being one.

The answer isn’t as straightforward, yet AI users tend to get the credit. This has resulted in creators whose works were “stolen” filing lawsuits against the AI tool’s developers (quote on “stolen” because it’s still highly debated). Publishers have also begun fighting back by purging AI-generated articles from their sites.

But while the obvious solution may be to refrain from using AI, not everyone has the luxury of doing so. Specific fields like marketing need to keep up with changing consumer trends. They don’t have the luxury of waiting for people to be fully trained, let alone experienced.

The fact that the time to opt out of AI is long past, as Pace University philosophy professor and AI ethics specialist James Brusseau told the BBC, doesn’t make it better. Businesses either embrace technology or struggle to keep up with the times. (2)

Search’s Response to Plagiarism

Given Google’s insistence on quality content, surely it penalizes plagiarized content.

Well, sort of.

Officially, it doesn’t have a function that punishes plagiarism in the same league as, say, the Panda and Penguin updates (as of this writing, anyway). That said, it does have some mechanisms in place to “deprioritize” duplicate content.

Notice how I said deprioritize instead of penalize. It isn’t necessarily breaking the rules, but it won’t do your content any favors in terms of SEO. John Mueller addressed this in an SEO Office Hours episode back in 2022. I’d recommend you watch the whole video below if you have the time; if not, skip to 7:43.

Let’s unpack his insight. First, copying or duplicating your own work doesn’t constitute a breach of Google’s guidelines. It can’t even be called plagiarism because you can’t steal something from yourself (unless you hate yourself that much, but that’s beside the point).

More importantly, Mueller stressed that Google places weight on adding value. Duplicate content doesn’t result in a penalty, as it’s a common practice for making local webpages. Otherwise, he pointed out that a handful of articles with added value to the reader is more search-engine friendly than a bunch of copies.

One instance when duplicate content constitutes a penalty is when the website employs doorway pages. These cookie-cutter pages have slight variations but little to no intent to provide something valuable to readers. It’s one thing to craft a page for a local audience, but it’s another to copy-paste a page and change a few words.

There’s this long-running joke among SEO professionals about one such guy walking into a bar…followed by over a dozen synonyms of the word “bar.” Doorway pages in a nutshell.

Source: Someecards

You should also know that today’s consumers are smarter. They don’t appreciate content that wastes their time—read: content that doesn’t satisfy their needs. Think about it: how can a consumer trust Expert A on a subject if the latter’s answer was taken from Expert B? Wouldn’t it be better for the consumer to go to Expert B instead?

Be Ethical, Professional

You can argue that you’re just following what’s trending, but you can be better. Plagiarism is never the answer because, if anything, it shows a brand’s weakness by repeating what’s already been mentioned. That doesn’t inspire confidence among your target audience.

Fortunately, this isn’t our first foray into plagiarism in SEO.Years ago, we ran a blog post on how to avoid it when creating content. Upon closer inspection, I can confirm that the best practices discussed there still apply (with a few updates).

Use Your Own Knowledge

I can’t claim that my subject matter expertise is on par with the industry’s big names like Danny Sullivan (currently a director within Google Search, according to his LinkedIn page) or, of course, John Mueller. But that doesn’t stop me from taking their expertise to heart.

Going through the relevant information helps me formulate my own analysis and examples before writing the first paragraph. Don’t worry about your insights not being equivalent to those of prominent personalities in your industry. Only you can add a unique twist to your content, and only you can be credited for that.

I’d go so far as to say that this is good advice for writing in general, whether writing about other topics or writing fiction. As someone who spent his youth creating fan fiction, one immutable rule is to understand the franchise you’re borrowing for your story. Diehards can be nitpicky about the slightest errors.

Choose Your Sources Wisely

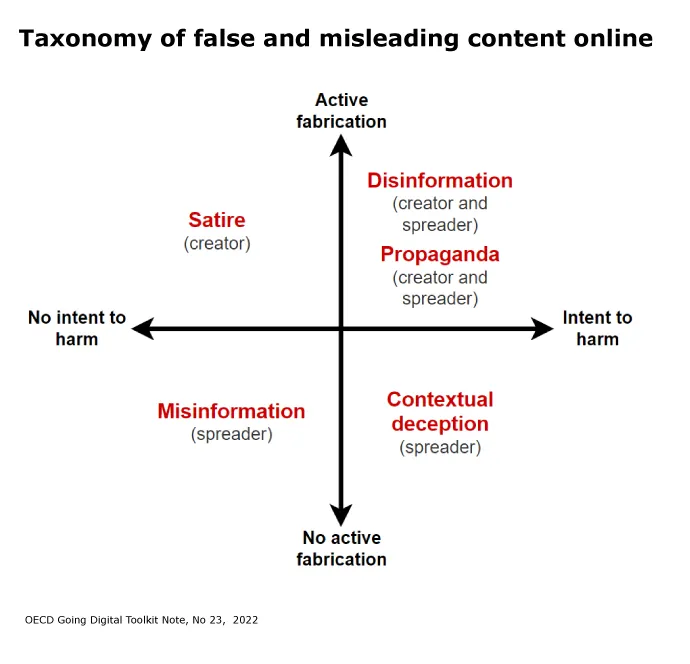

It’s one thing to get a good grasp on your topic, but it’s another to get your information from reliable sources. Disinformation (or attempts to disinform, at least) is all over the place, and AI is making its production easier.

“Wait a minute, don’t you mean misinformation?” That’s also a problem, but as the chart below shows, they’re two different things.

Source:Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Whether mis- or disinformation, the Internet can’t afford to enable the spread of both. And when consumers realize something questionable about your sources, you’ll be up a creek trying to address their concerns.

Just as gauging content quality has E-E-A-T, measuring a source’s reliability has CRAAP. Developed in 2004 by Sarah Blakeslee, then a librarian at California State University, Chico, CRAAP consists of five criteria: (3)

- Currency: The source was published not too long ago

- Relevance: The source could help answer the question

- Authority: The source was made by a relevant expert

- Accuracy: The source’s claims are supported by evidence

- Purpose: The source’s author makes their intentions clear

Higher-tier sources like research papers and government publications are more likely to meet all five criteria. But if you want to be more reputable in your choice of information, consider primary sources. For example, a news story talking about a big-ticket merger should have official statements from the merging companies as a primary source.

Always Cite Your Sources

Once you start crafting your content, always remember to cite who said what. Quote them word for word or, at least, paraphrase their statements while linking to the primary source. Never put words into a source’s mouth.

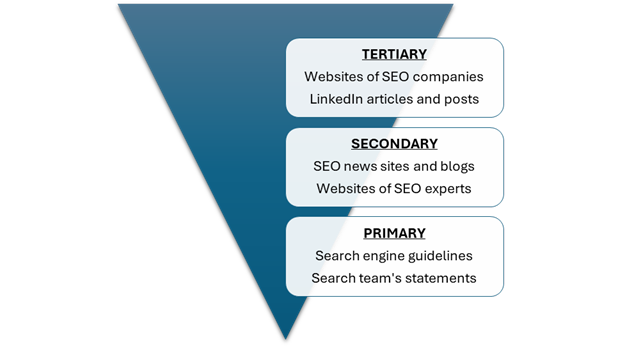

Whenever I make these blog posts, I rely on news sites—general or niche—for information. However, using these sources isn’t my priority; instead, I use them to trace the information back to a primary source. For example, this is how I typically hunt for such sources.

While other sources provide the information, tracing it to the primary source confirms it. If no primary source can be traced, settle for the secondary source but with caution. Either way, citing the source reduces your risk of getting in legal trouble for plagiarism and worse charges such as libel (provided you state the facts responsibly).

Give Credit Where It’s Due

Taking credit for someone else’s good statement may be tempting but is downright wrong. Honing your expertise is a slow process that involves admitting that you always have much to learn from others. Say no to plagiarism, even in this AI-dominated day and age, and give credit where it’s due.

References:

1. Bigelow, A. Mark Twain: A Biography. Complete [Internet]. Gutenberg.org. 2021. Available from:https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/2988/pg2988-images.html

2. Bearne S. The people refusing to use AI. BBC [Internet]. 2025 May 5; Available from:https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c15q5qzdjqxo

3. Meriam Library. Evaluating Information – Applying the CRAAP Test [Internet]. Meriam Library. California State University; 2010 Sep. Available from:https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf

Subscribe to Our Blog

Stay up to date with the latest marketing, sales, service tips and news.

Sign Up

"*" indicates required fields